Making Change Problem, Part I

Published: Sat, Jul 31, 2021

When approaching a problem, it may be tempting to work within the constraints of the examples given. While a solution may arise from that looks correct, you may be leading yourself astray. I recently worked through the change problem which is an example of this.

The change problem

You are given 3 denominations of coins to work with. You are also given a target value. You are supposed to find out the least number of coins that it takes to get to the target value. To keep things simple, it is also assumed that all target values have solution. You'll always be able to make change.

A starting point

It is common to see the starting coin denominations be [5, 10, 25] with various target values to test against 5, 15, 50, etc.

At this point, it may be tempting to do a comparison based on the largest denominations extractable. Compare the target value to the largest coin- if it is greater, that's your first coin! If not, you go to the next lower coin. You take the remaining value after subtracting the coin and then start the process again. Rinse, wash, and repeat until you get to zero.

Given coins of [5, 10, 25], a target value of 45, it would go something like this:

- Start with 45 and change = nothing

- Is 45 greater than or equal to 25? YES: change = [25], remaining value = 20

- Is 20 greater than or equal to 25? NO: compare the next lower coin...

- Is 20 greater than or equal to 10? YES: change = [25, 10], remaining value = 10

- Is 10 greater than or equal to 25? NO: compare the next lower coin...

- is 10 greater than or equal to 10? YES: change = [25, 10, 10], remaining value = 0

- Remaining value is 0 so return the number of coins which is 3.

Here is an implementation of this approach:

const coins = [5, 10, 25];

function makeChange(coins, amt){

coins.sort((a,b) => b-a) //from highest to lowest

let remaining = amt;

let change = []

let coinsIndex = 0

while(remaining > 0){

if(remaining >= coins[coinsIndex]){

remaining -= coins[coinsIndex];

change.push(coins[coinsIndex])

} else {

coinsIndex++

}

}

return change.length;

}

makeChange(coins, 45)

//--> 3Greedy

It works for that particular group of denominations but will not with others. Sometimes the optimal combinations will not involve the largest coins. If we change out the denominations to [1, 6, 10], the above algorithm will not return the correct solution. If given a target value of 12, it will return [10, 1, 1], or three coins. A change of [6,6], or 2 coins, is the correct solution.

The problem is that the algorithm is optimized without taking into account the larger picture. Working from the largest denomination down is an optimization that works specifically for [5, 10, 25], but not the right one for the larger problem at hand. In this case, it is called a greedy algorithm. Greedy algorithms are usually intiutive in nature and where our minds first go when working on a problem. They have their time and place but not here.

Brute force

The coin problem demands that the algorithm looks at ALL combinations possible and then return the shortest one. This is accomplished most easily through recursion. This applies a portion of an algorithm to repetitious steps until some base condition is met. We cannot be certain about how many coins it will take to make change, it is not just a matter of nesting a loop with in a loop so many times. We have to set up a condition to where the recursive portion of the code knows when to complete and give back values we can work with.

Please note that I am taking advantage of closures to minimize my code's footprint on global. If you are unfamiliar with closures, more info can be found on Mozilla Developers Network. Also, rather than just returning the coin count, I am returning an object that consists of all the combos, the shortest combo, and the iteration count (how many times makeChange() runs). I wanted to have access to those values so I can analyze the algorithm's performance.

const makeChangeClosure = (coins) => {

let combos = []

let shortestCombo = []

let iterations = 0

const makeChange = (value, aggregator = []) => {

iterations++

coins.forEach((coin) => {

let remaining = value - coin;

if(remaining > 0){

bruteChange(remaining, [...aggregator, coin])

} else if (remaining === 0) {

combos.push([...aggregator, coin]

if(aggregator.length < shortestCombo.length || shortestCombo.length === 0 ){

shortestCombo = [...aggregator, coin]

}

}

})

return {shortestCombo, combos, iterations}

}

return makeChange

}

const bruteChange = makeChangeClosure([10,6,1])

const bruteChange12 = bruteChange(12)In the code above, makeChange() is doing most of the work. It takes in a value, and an aggregator array. As it matches a coin, it pushes that coin's value into the aggregator and subtracts it from the value. Those values are then fed back into the same function, accomplishing the same thing. All the while, through the power of recursion, the algorithm is creating branches that represent all possible coin combinations.

This happens repeatedly until a branch's remaining value = 0. At that point, that branch's combinations are exhausted and the combo is pushed into the combos array. The combo also examined to see if its length is shorter than the length of the shortest combo already collected. If so, the value is then set. If not, it is ignored.

Brute force is expensive

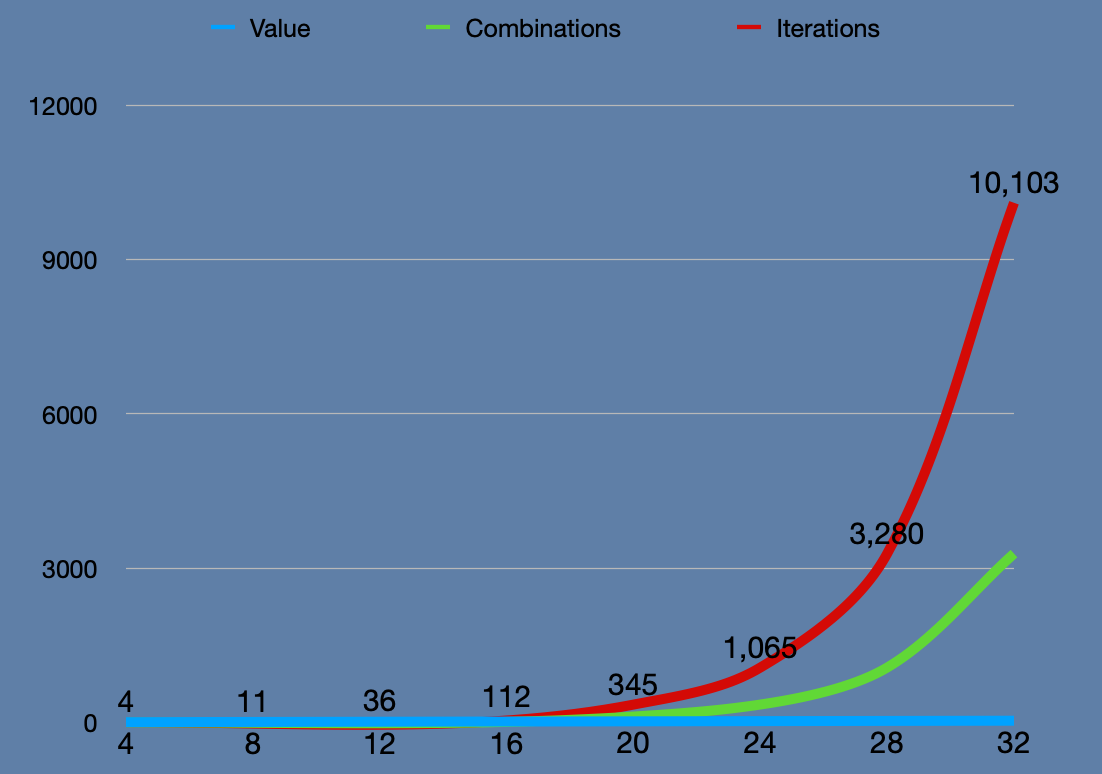

This solution is correct but it struggles with relatively modest values. It is because it is a roughly an exponential, O(n^2), solution. As more values are used, the number of iterations the algorithm must go through increases exponentially. O(n^2) is a rough approximation as there would be a lot of math to come to a highly accurate assessment, but it is close enough for my purposes. See the table of values to iterations below given the coins 10, 6, 1:

| value | combinations | iterations |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 1 | 4 |

| 8 | 4 | 11 |

| 12 | 12 | 36 |

| 16 | 36 | 112 |

| 20 | 113 | 345 |

| 24 | 346 | 1065 |

| 28 | 1065 | 3280 |

| 32 | 3281 | 10103 |

Visualized, one can see how fast the number of iterations increases relative to the value input. I made my browser unresponsive with a value of 78!

What's next for part II?

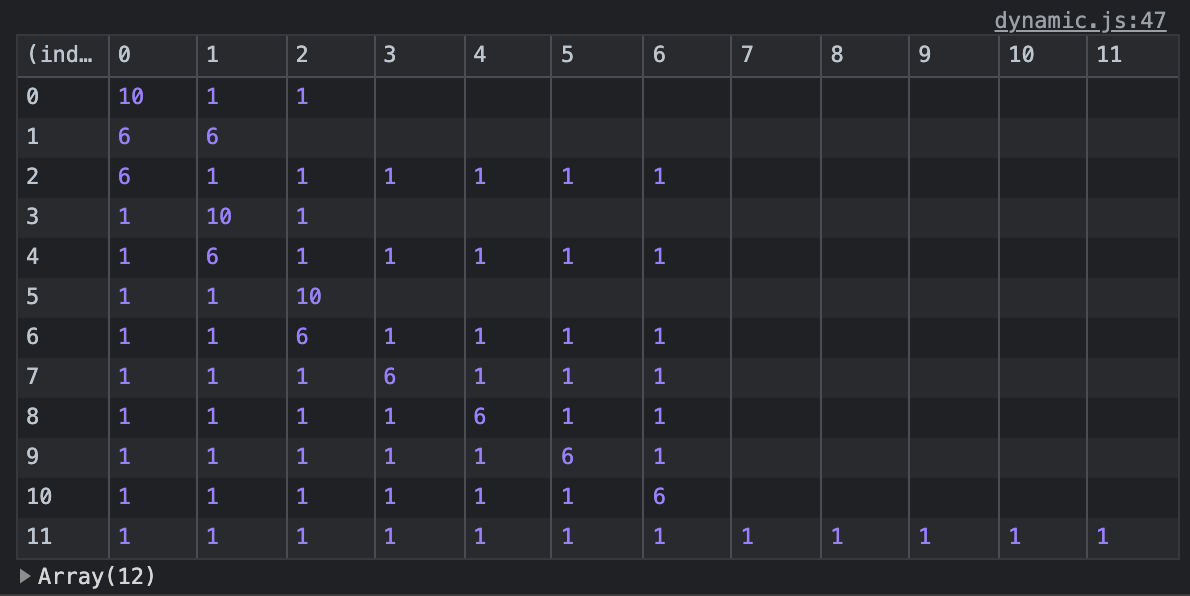

Optimization. When the recursion branches across all permutations, duplicates are bound to crop up. The table below shows the combinations made when the algorithm is given a value of 12.

Through various techniques some of the repetition could be avoided. For an upcoming post, I will tackle the solution's runtime complexity and make it easier to run.

Continue on to part II...

I'm open to work!

- Hi all! I am seeking a remote engineer position that can leverage a unique history of IT experience with several years of developing web applications.

- I've worked most recently with JavasScript, TypeScript, Python, PHP, and Ruby but am game to learn other scripted languages.

- Most importantly, I am all about making positive impact at organizations that see inclusivity as a strength rather than an obligation.

If you have room on your team and need someone that can contribute beyond just code, hit me up!